- Home

- Martha Bayne

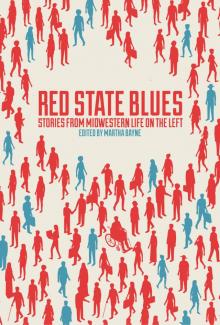

Red State Blues Page 3

Red State Blues Read online

Page 3

I remember exchanging looks with a girl from Tennessee. We tried to explain that, well, yeah, some people—including people we love—do watch Fox News, and they do think it’s the best place to get their information. We disagree with them, but we love them and want them to be safe and healthy and happy. Sometimes we’re alarmed by the things that come out of their mouths, though, and the violence with which those things come out.

I don’t know if it is better or worse to grow up in a place that does not share most of your values. I do know that it forces you to see people who are different from you as human, rather than as some faceless concept (like the mythic, monolithic “white working class,” or the occupants of something called “Trump Country”). They are your day-to-day life, the people you joke with on the afternoon bus and the people who sit by you in class. Sometimes you settle for rolling your eyes when they talk politics, because arguing with them is too exhausting. In rare triumphant moments, you stand up to a smarmy Republican teacher who takes for granted that everyone agrees with him, or at least that everyone will shut up and pretend they agree with him.

Since November 2016, “empathy” has become a loaded word. Empathy is something western Pennsylvania taught me. As a writer, empathy is something I can’t help, and can’t afford to lose; I want to understand other people. Flat characters are for formulaic superhero movies with Good Guys and Bad Guys, not the stories I want to tell.

But empathy does not mean a free pass. My empathy for your real pain and hardship doesn’t get you off the hook for deciding that a candidate’s racism, xenophobia, and misogyny weren’t that big of a deal, because you didn’t think they’d affect you directly, or just didn’t think they mattered that much. And nothing rings more hollow than a think piece pleading with the people in the line of fire—black folks, Latin folks, immigrants, queer and trans people, Muslims, women, Jewish people, people who need Medicaid for life-saving services—to empathize with those who put them there. Why should they be obligated to peer into the souls of people who couldn’t be bothered to do the same for them?

In the summer of 2016, I drove from Massachusetts to Greensburg. The last leg of the journey took me from featureless, gray Route 22 onto Route 119, through little towns like Crabtree and the rolling green fields that signal home to me. I used to get lost on purpose in these hills coming back from college, soaking in the scenery. This time, every pocket of civilization I passed was scattered with Trump signs, like clusters of fungus on fallen trees. This wasn’t surprising; after voting twice for Bill Clinton, my county had gone Republican since 2000. I have always known who my neighbors are. But I felt sick in a way I hadn’t felt about the John McCain signs that sprouted all over my hometown in 2008. I might have rolled my eyes, or sighed, at McCain and Mitt Romney, but I did not feel afraid at the sight of them.

On election night, I watched the results with my colleagues at our office in Springfield, Massachusetts. I didn’t leave until Pennsylvania had been called, around 1:40 a.m. The next morning, I began sorting through my emotions. I considered the facts. In total, just about six million people, half the population of Pennsylvania, had voted at all. The winning candidate’s margin of victory was narrow, not even a majority—just less than 49 percent of the vote to just less than 48. I knew all this, but still I felt, that morning, betrayed by my own skin.

But I am proud of what western Pennsylvania made me. I am proud of my mother, who took me to ragtag protests throughout my youth, who is so vocally opposed to this administration that acquaintances and friends often send her private messages on Facebook, thanking her for saying things they aren’t bold enough to say themselves. I am proud of my father, who provides medical care to kids in the poor, rural areas that voted hard for Trump, the areas in desperate need of help from someone who cares about them outside of an election cycle. I am proud of my friends and relatives who still live there, and of all the members of the community who do the crucial, unglamorous work of making people’s lives better.

What was killing me November 9, 2016, was the small, irrational hope I’d held that the people who sat next to me at my brother’s hockey games, drove me to and from practices, and came to my graduation party would be decent enough to look at Donald Trump and say, enough is enough. Yes, we are conservative, we are Republicans, but some things matter more than party lines, and this is not a normal Republican presidential candidate.

Some of them were decent enough, of course. But a lot of them were not. And the people of whom I’m thinking are not all members of that much-scrutinized White Working Class with all of their Economic Anxiety. They are all white, yes, but many live quite comfortably. Their cars are large, with trunks big enough to carry multiple hockey bags, and their spacious homes sit in immaculate housing developments. Some are old classmates who, in the culture vacuum of the suburbs, embraced a certain “redneck” identity that celebrated their realness, their true American-ness, which they demonstrate largely through drinking at country concerts.

I don’t know whether their feelings are changing now that white supremacists feel comfortable enough to openly display their colors all around the country, some of them saying outright that this administration has emboldened them to do so. I have stayed Facebook friends with some acquaintances from the area; there are times to unfriend and unfollow, but I am afraid of what happens if we all cut ourselves off completely from people with whom we disagree. One woman, who posted in November that she voted for the president based on his position on abortion, voiced disappointment and a sense of betrayal in August, in the days after Charlottesville. I haven’t heard much from anyone else.

Three years ago, when I got my tattoo, I figured the odds were better than not that I would never live in Pennsylvania again. Kids like me flee towns like mine all over the country, for all sorts of good reasons, and a lot of them don’t come back. My county lost more population between 2010 and 2016 than any other county in Pennsylvania. Some people leave seeking jobs. Others leave seeking safer places that will fit them better, or threaten them less; my queer friends from home left for bigger cities. I left in part because I wanted to explore a new place, to start over in a city where nobody knew me. Somewhere along the line, I put down tentative roots; the hills and old mountains in the northwest part of my adopted state have been a good enough facsimile of home. The fall of 2018 will mark my tenth in Massachusetts.

But now I can see myself in Pittsburgh. Maybe in a year, maybe further off, but I can imagine it. Maybe if I want to keep talking up my unromantic swing state, I need to put my money where my mouth is. There are people in western Pennsylvania, and in Ohio and West Virginia, who deserve better than a president who will play to their fears and anxieties in election season and strive to leave them without health care months later. They deserve someone who will speak honestly about how we got this way and provide real solutions, rather than taking the cowardly cop-out of casting immigrants and people of color as convenient enemies.

But maybe it is too easy for me to give a rousing speech from western Massachusetts, where Bernie Sanders dominated the bumper-sticker race from the start and won my town’s primary vote with ease. The week before Christmas in 2016, my brother and I were driving home through the center of the state—the white-hot core of Pennsyltucky, if you must—under an astonishing pink sunset that stayed with us as we wound west, past barns in picturesque fields covered with snow.

I tried not to think about politics. I wanted to fight for the land and sky themselves, to protect them somehow from harm. It is easy to romanticize from the highway, and easy to dismiss, or speak grandly, from hundreds of miles away. That day it was hard, maybe impossible, to hold everything I felt about Pennsylvania in my heart at the same time.

AMERICAN CARNAGE IN PENN’S WOODS: A HISTORICAL PARABLE

ED SIMON

“Were they not suspected of hostile designs? Had they not already committed some mischief? Some passenger, perhaps, had been attacked, or fire had been set to some house? On whi

ch side of the river had their steps been observed or any devastation been committed? Above the ford or below it? At what distance from the river?”

—Charles Brockden Brown, Edgar Huntly, or, Memoirs of a Sleepwalker (1799)

“He sees where blows with Rifle-Butts miss’d their marks, and chipp’d the Walls. He sees blood in Corners never cleans’d. Thankful he is no longer a Child, else might he curse and weep, scattering his Anger to no Effect… What in the Holy Names are these people about? … Is it something in this Wilderness, something ancient, that waited for them, and infected their Souls when they came?”

—Thomas Pynchon, Mason & Dixon (1997)

Pennsylvania’s frontier in the decade after both the Seven Years War and Pontiac’s fearsome Indian rebellion was a paranoid place. In the 1760s, Pennsylvania was not yet even a century old, but the settlers had feared the howling wilderness since they laid the first red brick of Philadelphia. As it was in New England and Virginia, here in the middle colonies fear of not just nature but the Indian Other would be the birthright of these new Americans. King Charles II—that drunken, womanizing, dandyish monarch—granted a proprietary charter for the colony to that stolid, sober Quaker William Penn, in recognition of naval service that the latter’s father had performed in the 1650s, which resulted in Great Britain acquiring Jamaica.

Penn was on fire with that Inner Light of the Society of Friends, and he believed in Christ’s prophecy that swords would be beat into ploughshares, and though Penn took the injunction that “Though Shalt Not Murder” as absolute decree of the Lord, his new experiment in utopianism on the shores of the Schuylkill and Susquehanna is intimately tied to the blood-soaked success of his father on those warm Caribbean sands. After all, “Pennsylvania” was named by the King after the father, not the son, as many have assumed.

Though the colony was generously defined by an incredible diversity in religion, ethnicity, and language, there were also deep fissures that developed in the decades after Penn’s death. Tensions between white and Indian, English and Scots-Irish, Quaker and Presbyterian, east and west, and as always (and still) between urban and rural. For in what would be the largest private land owning in human history, this combustible combination would alight in terrifying, unprovoked violence one winter day in 1763, when innocent blood stained new snow red.

Right as dawn broke on December 14, a crisp, clear winter morning when winters were still cold, a masked group of vigilantes snuck into a Conestoga Indian village not far from where Millersville is today and killed six Susquehannock men, women, and children as they lay sleeping. The militia—prefiguring the posses that would later define America’s violent history—was composed mostly of settlers with Scots-Irish background from the borderlands on the western frontier of Pennsylvania. The Conestoga Indians they attacked hadn’t just laid down their arms; they had never picked them up to begin with. For if the shivering settlers at Fort Pitt had feared Chief Pontiac arriving from the west to cut their throats while they slept (and in turn decided to ameliorate their fears by inventing biological warfare, as the forks of the Ohio was the first place where smallpox blankets would be distributed amongst the natives), these murdered Conestoga at Millersville were good Christians who posed no threat to the men who killed them.

The theoretician of this murderous crew—who heard Iroquois war cries in their nightmares even when the Iroquoian spoken in Millersville was more often than not offered up in Christian prayer—was a minister named John Elder. Charmingly referred to as the “Fighting Pastor,” as if he were the mascot of some sleepy Christian liberal arts college’s football team, Elder was in reality by every definition of the word a genocidal war criminal guilty of ethnic cleansing. Elder preached his sermons in a town called Paxtang, and from a bastardized, Anglicized pronunciation of that place-name his gang would come to be called the Paxton Boys. In those frosty years after the French and Indian War, the Paxton Boys marauded through the backcountry, massacring innocent Indians and murdering those they viewed as white race traitors. Settlers on the western frontier had suffered mightily during that war, and they sometimes did not receive the resources or assistance that they could have from the colonial government. But the Paxton Boys departed from mere martial logic and embraced the totalizing reasoning that justifies genocide.

As historian Fred Andersen writes, “The message of all these losses, for the colonists, could be reduced to the syllogism that lay behind the Paxton Boys’ plan… if good Indians did not harm white people, then the best Indians must be those who could do no harm, for all eternity.” Something occult had indeed developed in the backcountry. Surprise in Philadelphia can only be accounted to their not paying attention, and their not understanding their own relationship to men like the Paxton Boys, who would soon turn and threaten the city as well. As the violence spread, Rev. Elder refused to identify which of his congregants had blood on their hands from cut Indian throats or who had scalps affixed to their belts as if they were animal pelts. For that the minister was relieved of his manse by the Presbyterian Church, who didn’t countenance the mutilation of praying Indians.

In the wake of the Conestoga massacre, Governor John Penn offered a reward for the capture of the Paxton Boys and ordered that the surviving Susquehannock be placed in protective custody at a prison in Lancaster. On December 24, Elder’s clan broke into the prison, and there they murdered and then mutilated the remaining Indians who had seen their friends and families killed by these same men only ten days before. Six adults and eight children were killed on Christmas Eve. Jesus may have loved the little children, but his minister broached no such affection, for an Indian infant was still first and foremost an Indian.

Participants in the lynching were never identified, but as one witness to their attack, William Henry, recorded, the posse of some two dozen were “well mounted on horses, and with rifles, tomahawks, and scalping knives, equipped for murder.” After the Paxton Boys had departed from their crime, Henry was able to take stock of the hideous scene. He came upon the corpse of Will Sock, beloved among whites and natives alike, “on account of his placid and friendly conduct.” Next to the old Indian and his wife were two children “of about the age of three years, whose heads were split with the tomahawk, and their scalps all taken off.” He saw the corpse of a man, “shot in the breast,” whose legs and hands were chopped off, and who was finally shot in the mouth with a rifle, “so that his head was blown to atoms, and his brains were splashed against, and yet hanging to the wall, for three or four feet around.” There had been peace with the Indians for a decade, and these Susquehannock, who lived among the men and women of Lancaster in a spirit of mutual affection, had endured their illusory protection in that prison cell by singing psalms and reading their Bibles. And yet the Paxton Boys—and the demagogue who had inspired them—indulged in this orgy of supposedly preemptive violence to protect the safety of the white settlers on the western horizon.

Elder responded to the latest atrocity by washing his hands of it. The minister saw the tomahawking of a friendly old man, the scalping of toddlers, and the decapitation of an innocent Indian not as his fault, even if he’d been preaching a scripture of cleansing atrocity for months now. Rather, it was the fault of those elite city-dwellers off in distant Philadelphia, those rootless cosmopolitans who didn’t understand the reality of life in the backcountry. He wrote to the governor that “Had Government removed the Indians, which had been frequently, but without effect, urged, this painful catastrophe might have been avoided.”

Elder implored, “What could I do with men heated to madness? All that I could do was done.” Furthermore, the Philadelphians didn’t understand that the Paxton Boys aren’t violent men, for “in private life they are virtuous and respectable; not cruel, but mild and merciful.” Though the massacre was “the blackest of crimes,” Elder justified the tomahawking of children as simply one of those “ebullitions of wrath, caused by momentary excitement.” Really, Elder informed Penn, you had to kind of be there to

get it.

The Paxton Boys took aim not just at the Indians but at their fellow white colonists as well. Literary scholar Scott Paul Gordon explains that they reserved just as much opprobrium for who we might think of as “liberal” whites, writing that the “Paxton Boys targeted whites, English Quakers and German Moravians, when they believed that these groups, too, jeopardized the security of the backcountry.” Elder had triggered a culture war. Educated, worldly, sophisticated inhabitants of a city like Philadelphia, used to hearing not just English but German, and Swedish, and Dutch, and indeed the Algonquin and Lenape languages of the Indians, were horrified by the atrocities to the west. Shortly after the New Year, a popular pamphlet titled A Narrative of the Late Massacres, in Lancaster County was read from Walnut Street to Rittenhouse Square, in taverns and coffee shops and churchyards. The writer, a revered printer named Benjamin Franklin, feared not the Indians, who had lived in peaceful coexistence with settlers since Penn’s original commission, but rather the “white savages from Peckstang and Donegal.” Placing their trust for protection with the “good” whites, the Indians found themselves slaughtered by the savage ones. The author’s lament is that the natives “would have been safer, if they had submitted to the Turks; for ever since Mahomet’s Reproof to Khaled, even the cruel Turks, never kill Prisoners in cold Blood.” Pennsylvania may be where the lamb was to lay down with the lion, a peaceable kingdom, but in Lancaster those “poor defenceless Creatures were immediately fired upon, stabbed and hatcheted to Death!”

These Paxton Boys fetishized their weapons and their masculinity and most of all their whiteness. They saw no compunction in putting innocent men, women, and children to the blade so as to preserve whatever they imagined and defined their sacred honor to be worth. They were “barbarous Men who committed the atrocious Fact…. Then mounted their Horses, huzza’d in Triumph, as if they had gained a Victory, and rode off—unmolested!” A Narrative of the Late Massacres was a furious document, which reminded its readers that “Wickedness cannot be covered, the Guilt will lie on the whole Land, till Justice is done on the Murderers. THE BLOOD OF THE INNOCENT WILL CRY TO HEAVEN FOR VENGEANCE.” If the Paxton Boys and their defenders were wrong about their fear of supposed, imminent Indian attack, then they were correct that the genteel inhabitants of Philadelphia were unaware that in the backcountry a malignancy was growing, not among the Indians but among the settlers, who increasingly festered in resentment against enemies imagined. And where there are enemies imagined, soon there will be enemies discovered (or invented). And then blood will be shed. The Paxton Boys had practiced on Indians, but Franklin feared that their rage would soon be turned against those whom the Paxtons believed protected the Indians. He turned out to be right. The Paxton Boys would soon march on Philadelphia.

Red State Blues

Red State Blues