- Home

- Martha Bayne

Red State Blues Page 2

Red State Blues Read online

Page 2

The Central Time Zone states fell into place next. Kerry grabbed Illinois, but Bush routed him in Indiana. Iowa was close, but went red. Bush cleaned up in Kansas. Missouri wasn’t as tight as some thought it might be, and Bush easily took the state.

But Ohio was still too close to call.

The polls then closed in the Mountain Time Zone. No surprises in Idaho or Montana or Nebraska, where Kerry voters needn’t have bothered. New Mexico and Nevada were too close to call, and would stay that way for hours. But when the West closed up and California went to Kerry, as everyone knew it would, and Oregon and Washington turned blue, it was game on. New Mexico and Nevada were still up in the air, but with Pennsylvania’s twenty-one votes firmly in Kerry’s column, suddenly it was a numbers game.

It all came down to Ohio.

CNN.com posted county-by-county results, which updated with alarming frequency. I eschewed all other coverage, instead keeping my eyes focused on the monitor and my finger on the mouse. The smaller, rural counties tallied up some large pro-Bush numbers. Dubya took seventy percent or more of the votes in Auglaize, Clermont, Clinton, Hancock and Holmes. It was closer in the suburban counties, but Bush clung to leads in Lake, Medina, Butler and Delaware. The cities largely went for Kerry, with Franklin, Mahoning, Lucas, and Summit counties giving the challenger well over fifty percent of the vote, and because of the huge population differences between places like Columbus and Knox County, whose total population was less than 30,000, the margin stayed razor thin.

It all came down to Cuyahoga County.

I did the math in my head. If Kerry could pull seventy percent of the vote in my home county, he just might win this thing. This happened in 1964, with LBJ winning almost half a million votes. I thought about line that morning, in the rain. The line was confusing. People had to go to the back of the line and wait all over again. Did it get worse as the day went on? Did it get more confusing? What if enough voters had been turned away to keep Kerry from the seventy percent I was figuring he needed to win?

I thought about Conspiracies, Crimes and Cover-Ups again. I thought about the chapter in which it’s outlined how shifting a few thousand votes in key areas could’ve swung the ’88 election for Dukakis. I had the sinking feeling that “they” had picked their president.

Who are “they?” The millionaires and billionaires behind the “Swift Boat” attack ads on Kerry’s service in Vietnam. Those behind the official-looking notices sent to people, voters, in the Columbus area, explaining that due to the expected high turnout, registered Democrats were to vote on Wednesday, November 3rd. “They” are the dirty motherfuckers who sent out letters on bogus Lake County Board of Elections letterhead telling newly registered voters that they had been “illegally registered” and would not be eligible to vote until the next election. “They” are the employees in the Secretary of State’s office who decreased the number of voting machines available in Franklin County, so that machines were running at 90-100% over capacity, resulting in waits of three or four hours or even longer. The result was that Franklin County voter turnout was just over 60%, fully ten percentage points lower than the rest of the state. “They” are those responsible for successfully challenging individual voter registrations, resulting in over 155,000 so-called “provisional” ballots being issued, the vast majority of these occurrences being in urban centers. “They” are the those that purged 168,000 voters from Cuyahoga County between 2000 and 2004, resulting in mass confusion at the polls, with people, voters, showing up at the wrong precincts, waiting in the rain for hours, being told that they were no longer registered and subsequently adding to the many thousands of provisional ballots being cast, with fully one-third of that number being discarded (doubling the percentage from four years earlier). “They” are the 13,500 rural Southwest Ohio Republicans who voted for both Dubya and Democratic Chief Justice candidate C. Ellen Connally, a liberal Clevelander with little to no name recognition in a place like Sidney.

I picked the president, and “they” picked their president.

I watched the numbers swell for Kerry in Cuyahoga County. I wished I’d been able to go to the election-eve rally in downtown Cleveland with Bruce Springsteen, where tens of thousands of Kerry supporters overran Mall C, the Boss reminding the crowd to “believe in the promised land.” But votes could be shifted, maybe not by hanging chad this time, but maybe just by Issue One and disenfranchisement and purposefully long lines. I started to sense my old cynicism welling up, feeling that my vote wouldn’t matter. “They” had picked their president. The numbers continued to swell for Kerry in Cuyahoga County, but I’d seen the lines that morning at Forest Hill, and I knew without being told that there were lines elsewhere.

More than anyone else, the “they” of Ohio were represented by one man: Secretary of State J. Kenneth Blackwell.

It was J. Kenneth Blackwell who sent a letter threatening to fire the entire Cuyahoga County Board of Elections if they accepted provisional ballots in precincts other than where those voters were registered. It was J. Kenneth Blackwell who sent out voter registration forms, which he later refused to process because they were printed on incorrect paper stock. It was J. Kenneth Blackwell who was behind the Cuyahoga County voter purges, in which some neighborhoods saw as much as thirty percent of their numbers disenfranchised.

It can’t have been a coincidence that those Collier brothers in Miami were witness to the “hanging chad” phenomenon a full twenty years before it occurred again in the same state. It can’t have been a coincidence that thousands of inner city Ohio voters, reliably Democratic voters, were purged from the rolls just in time for the general election. It can’t have been a coincidence that J. Kenneth Blackwell would fight so hard in court to preserve his “proper precinct only” rule about provisional ballots. It can’t have been a coincidence that there were already twenty-minute lines so early in the morning at Forest Hill Church, where I was among what might have amounted to about a twenty-five percent white minority. It can’t have been a coincidence that so many voters would swear out affidavits to the effect that their electronic voting machines would record either “no vote” or Bush votes each time they attempted to vote for Kerry. It can’t have been a coincidence that tens of thousands of Bush voters didn’t bother to vote either way on something as controversial as Issue One. It can’t have been a coincidence that there were no bilingual translators at heavily Latino precincts. It can’t have been a coincidence that the lines to vote in Gambier, near Kenyon College, lasted until well after midnight, while at nearby Mt. Vernon Nazarene College there were no lines at all from open to close.

Before I went to bed that night, I checked CNN.com one last time. Sixty-eight percent for Kerry in Cuyahoga County. On TV, reports were saying that, as the precinct results neared 100%, the election would remain too close to call for many hours. Others were already calling Ohio for Bush, some numbers showing Dubya ahead by over 200,000 votes. Only the provisional ballots remained. It was still possible, but increasingly unlikely, that Kerry had the numbers.

When I woke, whatever momentum was there as I watched Cuyahoga County vote overwhelmingly for Kerry was gone. Those 448,000 votes wouldn’t do it. At around 11 that Wednesday morning, Kerry conceded the election to Bush.

Of course, it wasn’t over. There were lawsuits to be filed, books to be written, blogs to be published, theories to be theorized, and tears to be shed. In the months that followed, the official story codified around Bush’s superior campaign strategy and the push for Issue One, which passed with over sixty percent support. But underneath other stories emerged, themselves represented in the documentaries No Umbrella and …So Goes the Nation, as well as Michigan Congressman John Conyers’s book What Went Wrong in Ohio: The Conyers Report on the 2004 Election. That one is a thoroughly sickening read, if you’re so inclined. J. Kenneth Blackwell took a shot at the Governor’s mansion in 2006, and thank goodness, Ted Strickland and the people of Ohio handed our friend an ass-whipping.

; If Conspiracies, Cover-Ups and Crimes had taught me anything, it was that, no matter how hard the opposition tried, there would be times in which the people, the voters, would speak too loudly to be drowned out. We weren’t heard in 2004, but a presidential candidate even less likely than Bill Clinton would ride a wave of “hope” and “change” to the White House in 2008. Of course, my cynicism could never completely abate. I knew Barack Obama had taken too much Wall Street money during his campaign to effect real change, and that Bill Clinton was literally from a place called Hope. In the 2008 primary, I voted for Hillary.

As 2012 rolled around, though, I got nervous again. Former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney was, to that point, the single worst presidential candidate of my lifetime, and possibly anyone else’s. Need proof? Look at the parade of ne’er-do-wells that Republican voters attempted to award with their party’s nomination in the “Anyone but Mitt” days. Minnesota Congresswoman Michelle Bachman, Texas Governor Rick Perry, pizza executive Herman Cain, former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, and former Pennsylvania Senator Rick Santorum. It says something that people, voters, took time out of their daily lives to go to the polls and choose any one of these nitwits over Romney. Anyone but Mitt.

When Romney finally sewed up the nomination, his campaign hinted that he’d be a sort of political Etch-a-Sketch, that they’d be unburdened by fact checkers. At first I thought the idea that voters would be fooled by a candidate so willing to brazenly lie his way into office was absurd. After the conventions, when Obama started to open up extremely wide leads in all sorts of polls, it looked like a done deal, the sort of election where I could sit back and sort of pretend that it was 1996.

But it wasn’t 1996 or even 2004. It would have been easy to allow my cynicism to take over during the 2012 campaign, especially living in Northeast Ohio. The Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision opened the floodgates for a ceaseless and increasingly absurd series of advertisements on television. Romney’s promise was fulfilled, as he ran a shockingly dishonest campaign that somehow saw him closing the gap in the polls.

This made little sense to me, apart from the frustration caused by having to pull ourselves out of the worst economic crisis that the U.S. has seen in almost a century. I shuddered to think that people could blame the current president for this, or really any president for that matter. Wall Street was to blame, pure and simple, and while I was annoyed that Obama’s administration was too willing to allow business to go on as usual, at least Dodd-Frank put some consumer protections in place. Romney’s choice of Paul Ryan as his running mate was telling—this Ayn Rand–obsessed bro had authored the most brutal budget plan imaginable. If any single one of the grandmas and grandpas who were sporting Romney/Ryan bumper stickers and yard signs had bothered to look over that thing, its slashing of Medicare alone would be enough to make their blue hair stand on end.

But the ads on TV were constant and loud and jarring and disturbing, on both sides. I tried not to let it make me cynical. I tried not to allow myself to become convinced that money would determine the election. I tried to believe that the people’s, the voter’s, voices would again be loud enough to be heard. I knew the election would come down to Ohio once again, because the sheer volume (and volume) of the advertisements showed it to be true. The Republican-led state legislature did their best to fall in line, creating a sufficient enough fear of voter fraud to enact Voter ID laws that felt more like a poll tax than anything else. John Husted was the young secretary of state, and while he was no J. Kenneth Blackwell, some of his maneuvers, including trying to truncate early voting hours in inner cities while allowing suburban locations to remain open practically 24/7, turned him into a Blackwell-light. It was beginning to feel very familiar.

I worried I’d see long lines in my Akron precinct. I worried there’d be many stories about voter intimidation in my old stomping grounds of Cuyahoga County, where weeks prior there’d been anonymously purchased billboards erected promising jail time for vote fraud. I worried about the Romney family investment in InterCivic, a voting machine manufacturer that had apparently supplied a couple Ohio counties. I worried that John Husted’s brazen attempt to increase historically Republican absentee voters by mailing out applications to every registered voter, whether they requested one or not, would have the desired effect. I worried that all of this added up to make 2012 feel strangely like 2004.

I needn’t have been so scared. I didn’t stand in line. There was no line. I walked right up. The sun shined brightly from morning until night. There was no dull, dreary, bone-chilling rain. I saw no voter intimidation, no scuffles over ID, no poll watchers bothering people, voters, outside of my precinct.

I again turned to CNN.com to follow the results. It was obvious to me within ninety minutes of the polls closing that the president would win re-election. There’d be no late night, nail-biting outcome. I could go to sleep early. I was no longer nervous, no longer worried. The people’s, voter’s voices, were heard.

We picked the president. I picked the president. On a sunny day, I walked from my beautiful home that I share with my lovely wife and our darling baby boy to a line-free polling place. I picked the president. “They” tried, again. “They” failed.

THE PENNSYLVANIA I CARRY WITH ME

ANNIE MAROON

Five years after I left, I got Pennsylvania inked into my skin. It was my second autumn post-college, and the notion that I might never live in my home state again was sinking in. So I decided to carry the state outline on my left shoulder, with the major rivers of the western third, where I grew up, drawn in blue.

I knew by junior high that I would leave Greensburg as soon as I was old enough. Both of my parents left the states where they grew up by their early twenties. My mom left Ohio for New Orleans, and my dad departed West Virginia for North Carolina. (Both eventually circled back to Pittsburgh; that part of the arc is only now beginning to seem relevant to me.)

At eighteen, I chose Boston. I almost never got homesick in college. That came later, once I became what you’d call a permanent resident of Massachusetts rather than a college kid. I spent a summer in western Massachusetts thinking about the mountains and creeks I grew up with, thinking about a cockeyed, hilly city where three rivers intersect, crossed by iconic bridges. I missed the geography, and I missed the people. My brother and I had left, but almost my entire extended family lives within a few hours of Pittsburgh.

And I thought a lot about the realization that hit me when I was seventeen and about to leave: that I would always be shaped by this place. I could roll my eyes and despair over the people around me in my rural-suburban county who never seemed to want to travel farther away than Pittsburgh. I could cast around for something fun to do with friends and wind up at the mall or the 24-hour Eat ‘n’ Park, because there was nothing else. But all that was part of me. I never wanted to get so far from home, mentally, that I forgot that.

Some states are iconic. Their names and shapes are evocative, synonymous with a way of life. Pennsylvania doesn’t have that. It’s a big state, but not big enough to have the outsized fantasies attached to it that California, Texas, or even Alaska have. It has major cities, but no New York or Chicago or Los Angeles. It’s a perpetual swing state, voting Democratic in presidential elections all my life (until 2016), but never overwhelmingly enough to gain a reputation for it. People sometimes see the western part of my tattoo and ask if it’s Massachusetts, mistaking the Allegheny River for the Connecticut. Others have squinted at it, running through the middle of the country in their minds: Ohio? Colorado?

In college, most of the real East Coast kids thought I lived somewhere in the suburbs of Philadelphia. Westmoreland County isn’t flyover country the way that, say, Nebraska is. From my parents’ house, you can drive to D.C. in four hours, New York City in six. But I learned the term “Pennsyltucky” early to describe my homeland (long before Orange Is the New Black used it for a character who, in the show, isn’t even from Pennsylvania, but Virginia)

. The term is a little too easy—dismissive of Kentucky as well as a huge swath of Pennsylvania—but while it irks me coming from New Englanders, I forgive it coming from others who grew up there.

The first election I really experienced was 2000. I was nine years old, in fourth grade, and it was the first time I realized just how different my family was from the families of my classmates. Kids talked, in the way kids do, about how they would vote for George W. Bush, because their parents were. In my fourth-grade class of about 25 kids, only two of us—my friend Marissa and I—were in Al Gore’s camp. (One other boy implied that he might have been with us, but he didn’t exactly want to stick his neck out. He and I are Facebook friends now, which means I see his pro-Trump posts.)

That was it: Marissa and I, taking whatever insults a bunch of vaguely conservative fourth-graders could hurl at us. We snapped back at our classmates pretty well, as I remember it, and the election went on for a month. At the end of it, George Bush was president, and I felt somehow separate from the kid who had entered the school year, terrified of having anyone pay attention to her. I was different, and now everybody knew it.

In eighth grade, my mother took me to a rally in downtown Greensburg before the 2004 election, where I hollered across the street at a friend’s father, who was waving an inflatable dolphin to mock John Kerry’s “flip-flopping.” I absorbed my parents’ lukewarm acceptance of the Democratic nominee and wore a Kerry button to school on Election Day. It was still pretty much just Marissa and me, but I was settling into my identity as one of Latrobe Junior High’s token lefties.

The summer before senior year, I spent two weeks at journalism camp in Washington, D.C., with kids from all over the country. I made friends from New Jersey and Los Angeles and Queens, all of whom were astounded when we watched the documentary Outfoxed. OK, but nobody really believes what’s on Fox News, they said. Nobody actually watches that stuff and thinks it’s true.

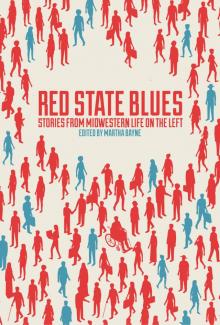

Red State Blues

Red State Blues