- Home

- Martha Bayne

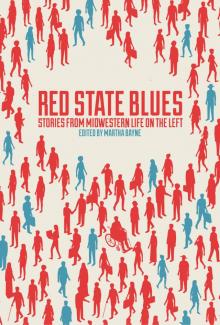

Red State Blues

Red State Blues Read online

OTHER TITLES FROM BELT PUBLISHING

The Akron Anthology

Car Bombs to Cookie Tables: The Youngstown Anthology

The Cincinnati Anthology

The Cleveland Anthology

A Detroit Anthology

Happy Anyway: A Flint Anthology

The Pittsburgh Anthology

Right Here, Right Now: The Buffalo Anthology

Rust Belt Chicago: An Anthology

The Cleveland Neighborhood Guidebook

The Detroit Neighborhood Guidebook

Folktales and Legends of the Middle West

How to Speak Midwestern

How to Live In Detroit Without Being a Jackass

In the Watershed: A Journey Down the Maumee River

The New Midwest: A Guide to Contemporary Fiction of the Great Lakes, Great Plains, and Rust Belt

What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

The Whiskey Rebellion and the Rebirth of Rye: A Pittsburgh Story

Copyright © 2018 Belt Publishing

All rights reserved. This book or any portion hereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. Printed in the United States of America.

First edition 2018

ISBN: 978-1948742061

Belt Publishing

2306 W. 17th St., Suite 4

Cleveland, Ohio 44113

www.beltpublishing.com

Cover and book design by David Wilson

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION by Martha Bayne

WHERE WE LIVE, WHO WE ARE

2004, EAST OF THE CROOKED CUYAHOGA by Chris Drabick

THE PENNSYLVANIA I CARRY WITH ME by Annie Maroon

AMERICAN CARNAGE IN PENN’S WOODS: A HISTORICAL PARABLE by Ed Simon

SEEING RED IN MICHIGAN by John Counts

THE BURGERS AT MILLER’S (OR, DEARBORN’S CHANGED) by Tara Rose

SEVEN YEARS IN INDIANAPOLIS by Allison Lynn

DOWNSTATE HATE by Edward McClelland

FAMILY IS FOREVER

BLOOD IS THICKER by Dara Aritonovich

AN ODE TO CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS, THE SECRET JEW WHO DIED OF SYPHILLIS by Trent Kay Maverick

APPALACHIAN YANKEES IN MICHIGAN by Wendy Welch

FROM MACOMB COUNTY TO DETROIT CITY by Amanda Lewan

KICK ASS: MY DAD, THE AMERICAN DREAM, AND DONALD TRUMP by Angela Anastoke Repke

DEMOLITION DERBY AND THE CHAUTAUQUA COUNTY POLITICAL MACHINE by Justin Kern

MIDWESTERN BUBBLES

THE OTHER “FORGOTTEN PEOPLE”: FEELING BLUE IN MISSOURI by Sarah Kendzior

“WE HAVE A GAY BAR HERE”: YOU DON’T NEED A COAST TO BE COSMOPOLITAN by Greggor Mattson and Tory Sparks

RACE AND KINDNESS IN YELLOW SPRINGS, OHIO by Mark V. Reynolds

FIBS AND CHEESEHEADS, FROM CHICAGO TO CHETEK by Bill Savage

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

WHEN ICE COMES TO TOWN: LESSONS IN RESISTANCE FROM ELKHART, INDIANA by Sydney Boles and Rowan Lynam

OTTAWA COUNTY: MAKE VACATIONLAND GREAT AGAIN by Vince Guerrieri

LIFE AND BELONGING IN KNOX COUNTY, OHIO by Sean Decatur

GUIDING A PROGRESSIVE PITTSBURGH THROUGH THE TRUMP ERA by Dan Gilman

A DEMOCRATIC HOPEFUL FROM RANCH COUNTRY by Christopher Vondracek

NEIGHBORS by Bridget Callahan

INTRODUCTORY COMMUNICATION: TEACHING ACROSS MICHIGAN’S URBAN-RURAL DIVE by Lori Tucker-Sullivan

CODA

ON BEING MIDWESTERN: THE BURDEN OF NORMALITY by Phil Christman

CONTRIBUTORS

INTRODUCTION

MARTHA BAYNE

A year and a half after the 2016 presidential election, Democratic voters across the country still carry visceral memories of the confusion, fear, and disbelief the election results engendered. Since November 8, 2016, pundits across the political spectrum have explored the electoral flip of traditionally Democratic states like Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Ohio with expressions of grave concern. The national media, unused to getting the story so wrong, has visibly and often inadequately struggled to understand and explain this newfound exotic constituency of blue voters who swung red, and tipped Donald Trump into the presidency.

But what about those voters who remained true blue? With a broad swath of the Midwest now painted as “Trump Country,” it’s easy for outsiders to forget the election’s razor-thin margins: 77,744 voters spread across Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania turned those Democratic states Republican. That’s less than the capacity of the University of Michigan’s football stadium.

Red State Blues speaks to the lived experience of progressives, activists, and ordinary Democratic voters. It pushes back against simplistic “Trump Country” narratives of the Midwest—a narrative from which the region’s rich history of grassroots, progressive politics has been erased. It gives the lie to lazy stereotypes about the white working class, who, by the way, aren’t the only people living here by a long shot, thanks to waves of migration, from the Great one of the mid-twentieth century to more recent arrivals from the Middle East, Central America, and South Asia. The diversity, grit, and resilience of the Midwest has been an open secret all along, and as the essays in this collection demonstrate, it’s a secret worth shouting from the rooftops.

By organizing the work here into a few loose categories, we’ve tried to bring a sense of, if not order, at least narrative chronology to a wide-ranging array of writing. Thus the first section, “Where We Live, Who We Are,” interrogates Midwestern identity in the context of the current state of national politics. Here, reporter John Counts travels to Northern Michigan in search of answers; Annie Maroon muses on loving and leaving western Pennsylvania, the place, she says, “that taught me empathy.”

Here at Belt, we initially (and lovingly) titled the next section “My $^@% Father Voted for Trump, Now What Do I Do?” … but after some second thought decided to go with “Family is Forever” instead. Whatever you call it, this popular—and painful—genre examines the personal toll of this polarized election. Here, Trent Kay Maverick takes a long, wry look at his own father’s penchant for “fake news,” and Amanda Lewan tries to sort out the familial memories and conflicts kicked up by her move from stark-red Macomb County, Michigan, to a fixer-upper in Detroit, the city her parents worked long and hard to leave.

“Midwestern Bubbles” looks at those lighthouses of liberalism that have long anchored the Midwest, and which seem curiously invisible of late to the outside eye. Places as small as a Cedar Rapids gay bar where you can get an after-hours HIV test are counted here, as are sites like historic Yellow Springs, Ohio—home of Antioch College—and, of course, the bright blue city of Chicago, whose relation to neighboring Wisconsin is, as Bill Savage explains, forever fraught.

Finally, we turn to the hope on the horizon. “Looking to the Future” examines the ways activists and politicians alike are working to change things for the better. Journalists Sydney Boles and Rowan Lynam walk readers through the fight against an ICE detention center in Elkhart, Indiana. Kenyon College president Sean Decatur shares his personal narrative of moving, as an African-American man, to majority white Knox County, Ohio. And Pittsburgh city councilman Dan Gilman lays out his blueprint for building a progressive city.

We close the book with one of the best pieces of writing on Midwestern identity we’ve read in recent years: Phil Christman’s “On Being Midwestern.” While not explicitly political, we wanted to include it as a grace note. Originally published in the Hedgehog Review in 2017, this lyrical essay lopes from personal experience through Marilynne Robinson, Thomas More, and Slate political commentary to really explore the limits and possibi

lities of place-based identity—how much of it is real, how much is aspirational, how much rooted to nostalgia. We’re happy he’s letting us reprint it.

This collection is, of course, not in the least exhaustive. There’s a lot more to read out there by, for, and about Midwesterners and their peculiar habits. If you’re from some other place, we hope this taste will give you context and perspective for what you’re seeing on the nightly news. And if you’re one us, we hope you see a little bit of yourself reflected here.

—Martha Bayne

WHERE WE LIVE, WHO WE ARE

2004, EAST OF THE CROOKED CUYAHOGA

CHRIS DRABICK

Today, I picked the President.

I stood in line, in the rain. It wasn’t so bad. It was morning, seven o’clock or so. The temperature was climbing, but it was still pretty chilly. I wore a hooded jacket. Even though the polls had been open an hour or less, already there were lines, which we were told to expect.

When I pulled my trusty Chevy Prizm into the parking lot at Forest Hill Church in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, the plethora of campaign signs made me wonder about the separation of church and state. Bush/Cheney. Kerry/Edwards. Yes on Issue One. No on Issue One. Eric Fingerhut for Senate. Re-Elect George Voinovich. Here I was, about to do my civic duty in a house of worship. There were people milling about, some in rain slickers, with clipboards holding paper that would soon be soaked by the precipitation.

There were three lines snaking outside of the church, with no signage or officials to explain the reason or reasons for the separation. I chose one, shoved my hands in my pockets against the wet chill and looked around. People were asking one another what line they were in. Was this the line for Precinct A or Precinct B? No one knew. The lines grew behind me, with many of the voters asking the same unanswerable questions. How long have you been here? When is this rain going to stop? Who are those people outside? Did you see the guy with the walkie-talkie? Who was he talking to? No one knew.

The line moved forward, still growing behind me. We shuffled inside, the hallway dark and wet from the shoes that had already trudged through. I pulled the hood off my head. The walls were those beige concrete bricks that comprise what seems like a majority of the interior walls of postwar churches. We moved forward, one at a time, slowly, surely. Confidently.

We were picking the president. I was picking the president.

As the hallway curved to the right, the reason for the three separate lines became clear. Forest Hill was housing three separate precincts that day. I was new to this area; I’d never voted in Cleveland Heights before. The rest of the crowd was confused. People, voters, looked to their registration cards, trying to match their precinct to the line they’d chosen. Some had guessed incorrectly. There was movement, shuffling. People, voters, remained calm. Some bowed their heads and moved to the back of the line, out into the rain, ready to repeat the twenty-minute wait that brought them to this point. The line might have grown by that point, meaning a longer wait. A little old lady, her dark skin shriveled over her five-foot frame, looked at me with quizzical eyes.

“What precinct are you in?” she asked.

I told her. She asked if I would let her in line in front of me. Of course I would.

I was nervous. There was talk of problems at the front of the line. Registrations lost. People, voters, in the wrong building. Poll workers already getting short, annoyed, tired, stressed.

There had been talk for weeks about electronic voting machines, made by Deibold, an ultraconservative corporation from my semiconservative hometown of Canton, Ohio. People, voters, were worried that there could be monkey business associated with the electronic voting machines. Deibold was known to have made large donations to the Bush campaign. That made computer-vote tampering possible, maybe even likely, to the not-so-closeted conspiracy theorist in me. My mind wandered to that battered trade paperback I’d carted around since undergrad, Conspiracies, Cover-Ups and Crimes by Jonathan Vankin, written in 1992, in which brothers Ken and Jim Collier recount their experience with vote fraud in a local election in 1980 in Dade County, Florida, punctuated by something called a “hanging chad.” In a book published in 1992. “Hanging chad.” I was nervous.

To be fair, I was never in love with Senator John Kerry as a candidate. I’d preferred Howard Dean, who seemed ready to embrace progressivism, and would have made for some dynamite debates with Dubya had he just steered into the skid after that disastrous scream in Des Moines following his disappointing third-place finish in the Iowa caucuses. Kerry was a little milquetoast, too willing to run toward the middle in an attempt to sway those multifarious independent voters. Sure he had the pedigree, the “JFK” initials, the foreign policy experience that was needed that year. But I always liked the idea of promoting governors to the presidency—Clinton, Dukakis, my long-wished-for presidential campaign of former New York Governor Mario Cuomo—and “JFK” here was a senator. But what was I going to do? I would’ve voted for damn near anyone with a pulse who opposed Bush/Cheney.

I was there to pick the president.

The line shuffled forward. The fluorescent light from the large dining room that held the voting booths was visible in the short distance, but the hallway was so crowded with people, voters, that I couldn’t see what sort of machines lay in wait. The earlier antsiness of the people, voters, was replaced by a calmer vibe, probably owing to the fact that we’d all settled in our proper lines.

It had been over a decade since I stood in a similar line. I didn’t know what to expect. There were stories about invalid voter registration, precincts in Cuyahoga County that would be swarmed by Republican foot soldiers sent to challenge votes. I thought about the rain-slicker, clipboard people milling around outside. They may have been just those vote-challengers, ready to storm in and begin their day’s work at any moment. The front of the line seemed calm, though, and there didn’t appear to be any real trouble ahead. It was early, and things could change.

It was time. I signed the book. They waved me through. The machines were not electric, nor were they old-fashioned punch cards. Optical scan. Like filling in a multiple-choice exam in a large undergrad lecture course. Introduction to Voting. At least there would be a paper trail.

I took some time to look over the wording for Issue One, an amendment to the state constitution, the so-called “Gay Marriage Ban.” I didn’t pause in order to consider my vote, as I considered turning this down to be a no-brainer, personally. However, polling showed the measure to be a slam-dunk to pass, and I wondered if the other voters were taking the time to look at the actual language of what it was they were voting on. The amendment eliminated legal rights for all unmarried couples. There it was, in black and white. The homophobes probably didn’t even realize that one was being slipped by them. It was a trick really; a ploy designed by state Republicans to make certain that fired-up evangelicals would turn out in droves and, while they’re at it, cast a vote for their boy Dubya. It made me a little mad, but I didn’t want to hold things up, so I filled out the rest of my ballot quickly and efficiently.

I picked the president.

The rain had slowed to a brief stop as I left Forest Hill Church. The rain-slicker crowd was still milling around the parking lot. Maybe they were exit pollsters, I don’t know. I quickened my pace, not wanting to be interviewed or accosted or anything else, got into the Prizm and sped off to my job.

My duty was done. I’d made my voice heard for the first time in over a decade. I couldn’t be silent any longer. I couldn’t allow my abject fear of jury duty frighten me out of registering to vote. No matter how much I may have wanted to, I didn’t feel apathetic anymore. It was fun while it lasted.

There was a lengthy period of time during which I was not registered to vote. By lengthy, I mean years. It might be true that I was not registered to vote for longer than I was registered to vote, but I can’t be sure because I don’t exactly know what causes a voter to become an ex-voter. Or when. But it was years.

&

nbsp; In and of itself, this might not seem absurd. I am, after all, a pristine example of a Gen Xer; born in 1971, overeducated and underemployed, a latch-key kid with all of the inherent and inherited irony that gave rise to things like twenty-plus years of The Simpsons. In retrospect, it sure was nice to have the requisite comfort that allowed us Gen Xers to be so cynical for so long. The bulk of my 1990s was spent in the bliss of political apathy. I didn’t vote in the 1996 general election, when Norm MacDonald’s Saturday Night Live version of Senator Bob Dole neatly summarized his “Chinaman’s chance” at winning the office. It was hard to vote against that guy.

Eventually, though, the Clinton presidency came to an end, the 2000 presidential election was decided in favor of George W. Bush by the Supreme Court, and it was a short ride from there to September 11, Afghanistan, the “Axis of Evil,” Iraq, and “Mission Accomplished.” The Clinton budget surplus came back to us in the form of $300 refund checks. Dubya had to go.

I remember little about my day at work that rainy November Tuesday. By the time my day was done, the polls were closed and I was ready to settle in and watch the results. I clicked around the networks and PBS for a bit, but it didn’t take me long to realize that the internet was providing the quickest returns. After some trial and error, I locked into CNN.com, where I was able to watch continuously updating returns broken down by state and county. My internet connection was speedy, and I smoked Camel Light after Camel Light, filling the small black ashtray that sat next to my second bottle of Goose Island Honker’s Ale. The polls were close, most of them showing a virtual statistical tie. In the final three Ohio polls before the election, Kerry carried a one-point lead in each, which in reality wasn’t worth a good goddamn anyway.

As minutes turned into hours, I watched the states turn red or blue. New York predictably went to Kerry. So did Massachusetts. Virginia was hard-fought but captured by Bush. New Jersey, closer than predicted, went for Kerry. Bush took North Carolina. All eyes turned on Florida, but Bush pulled comfortably ahead. Arkansas, Alabama, Georgia went to the Republican, too. Kerry held strong in Maryland, Maine and Michigan. But Ohio was too close to call.

Red State Blues

Red State Blues