- Home

- Martha Bayne

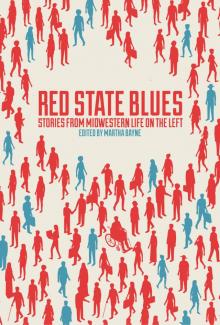

Red State Blues Page 4

Red State Blues Read online

Page 4

Andersen explains that as “word spread that the vigilantes intended to kill all the Indians in Pennsylvania, their popularity and their numbers mounted fast.” By early February fully 500 had assembled to march upon the largest city in colonial America, threatening to massacre every Indian who had taken up sanctuary in Philadelphia. One of the Paxton Boys wrote “When we go there, we’ll be sure to bring back Quaker scalps.” Another claimed that after that, the Paxton Boys planned to range some seventy or so miles to the north, where “not one stone should remain upon another in Bethlehem,” as there were designs to murder both Indians and the Moravians whom the rebels saw as the former’s protectors. Gordon writes that the Paxton Boys targeted a “multiracial set of victims,” where the nativist fury of the mob could focus on not just Indians, but also “Quakers, and Moravians,” all of whom would collectively come to “define the frontiersmen’s category of ‘enemy.’” When the Paxton Boys came to Penn’s city, the potential list of victims in this planned pogrom was long.

The mob was met at Germantown by an assortment of government leaders, including Franklin, and armed guards. Franklin negotiated with the rebels for the safety of both the city and the Indians hiding within. An understanding was reached—the men would spare the second largest city in the British Empire, the largest metropolis in English-speaking America, in return for assurances that the Paxton Boys would never be charged, convicted, or punished for what they did to the innocent Indians of Lancaster.

America—one huge Indian burial ground. Pennsylvania is the story of America writ small. Historian Peter Silver explicates what he calls “the anti-Indian sublime,” the dominant mode of American culture, where what an “American” is must always be violently defined against some exoticized Other. From the Indian to the slave to the papist to the Muslim and the Mexican. We’re in part so fearful of the Other because we know precisely what it is that we did to the Indian—not just in Lancaster, but in the Pequod War of seventeenth-century New England, or the plains wars of the nineteenth century—and we know our guilt. The very landscape heaves under the accumulated weight of so many ghostly corpses, where branches once dripped with human blood, and might yet again. Peter Silver recounts how a few years before the Paxton Boys crimes, a “raider named James Kenny passed up the Cumberland Valley from Maryland into Pennsylvania… he found that many people thought the snow-covered landscape around them charged with the presence of the dead.” Silver also recounts how the New American Magazine of Woodbrige, New Jersey printed a poem in 1758 entitled “On the Late Defeat at Ticonderoga,” memorializing felled settlers from the French and Indian War. The poet, travels through fields of “empurpl’d bodies,” the fetid, stinking, decomposing mass of corpses, white and Indian alike, which fill the fields of western Pennsylvania. Finally the poet comes to the banks of the Monongahela River, to encounter “gore-moisten’d banks, the num’rous slain,/Spring up in vegetative life again:/While their wan ghosts, as night’s dark gloom prevails,/Murmur to whistling winds the mournful tale.”

A gothic story, no? But then the story of America’s settling has always been a gothic tale. That anonymous poet of 1758 might as well have written in prophecy; his visions are that of Ezekiel in the desert. And like Ezekiel’s dry bones, those waterlogged corpses in the Monongahela would surely rise and walk again, haunting and compelling us in that cycle we dare not escape from. The poet’s narrative of defeated pioneers hacked to death by some unseen barbaric force served only to instigate men like the Paxton Boys as the American frontier continued to stretch ever westward.

Our stories haunt us, even if we don’t specifically know or even quite remember the shape of their narrative. And yet, those corpses—Indian and white—can’t help but “Spring up in vegetative life,” just as surely as Ezekiel’s field of dry bones would stand “upon their feet, an exceeding great army.” The Paxton Boys remain an exceedingly great army. They march on Lancaster and Philadelphia still. Whatever their new names be, wherever the new Lancasters and Philadelphias are. Nor are we innocent, ensconced as we are, surrounded by the comforts of our diversity and our education. Just as the Quakers let those low church pioneers fortify that boundary between civilization and its discontents, so too have we turned a blind eye to the distasteful and uncouth Paxton Boys of our own era, who brutalize whomever they deem the Other of today.

Herman Melville wrote of a “metaphysics of Indian hating” which defined the American experiment: a rancorous, poisonous worldview that now and again infects the body politic. In America, the Indians were only the first of many to be hated, and there are always and forever new Indians. Perhaps an argument could be made that large gatherings of diverse people affect a certain herd immunity to the worst of that disease, but that’s a secondary observation, for the Paxton Boys can live in any city, any neighborhood. They can live next door to you, drink coffee at Starbucks, shop fair-trade at Whole Foods, and hate you while they do it. The Paxton Boys wear khakis and drive nice cars. They part their hair. The Paxton Boys aren’t out there; there is no frontier, and there never has been. Only the vagaries and contradictions of the human heart. If you pay attention, you can meet the Paxton Boys even today, forever marching on the city, forever drawing closer. Too often we look the other way and let them scale the fortifications, where those whom we’ve promised to protect dwell. A promise of security for only so long. If the time comes, will you be willing to name every one of the Paxton Boys, or will you let them slink away, their victims not remembered, their crimes unnamed?

I never heard about the Paxton Boys until I went to get my PhD, but I still somehow knew the story. Not just because I’m a Pennsylvanian through and through, and am thus as privy to those ghosts as any other, but more importantly because I am an American, and that haunted gothic tale is all of our sinful inheritance whether we choose to collect or not. One could reduce an analysis of the contradictions of a place like Pennsylvania to that old joke about it being two big cities with Alabama in the middle, which I suppose is sociologically true, though equally accurate about all states and the country as a whole. Yet this parable should not be read as a reductionist allegory about urban versus rural, or town versus country, or liberal versus conservative. That some of that is in there, no doubt, would be accurate. But it’s not the whole story. Nor should it be read as being in the mode of the ever-popular white working class ethnography, where some coastal liberal makes condescending apologies on behalf of people with hateful beliefs by recourse to some misguided, sentimentalized class politics which is actually anything but. No, if anything this parable should make clear what’s incomplete about that particular genre, for those threatened and killed by the Paxton Boys were often working class, just as the good Rev. Elder was a distinguished, wealthy graduate of the University of Edinburgh. And as Gordon makes clear, the supreme irony is that many of the frontier Quakers and Moravians threatened by the Paxton Boys had previously been threatened by Indian attack during the Seven Years War.

What is most important to take from this parable is that there have been many Conestoga massacres. Being blind to those ensures that there will be many more in the future. While there are no Conestoga left to remember the names of those who died in December 1763, we remember those murdered in the hope that someday, somebody will remember us. And we pray that we can somehow exorcise the land of these ghosts, the hateful vigilantes and the tortured innocents alike.

SEEING RED IN MICHIGAN

JOHN COUNTS

The Iraq War veteran wore a bent-brimmed baseball cap that shaded his grease-covered face. I was interviewing the young vet-turned-mechanic, a defeated Bernie Sanders supporter, at his small town auto garage when a dark pickup pulled up into his driveway. The mechanic saw the truck and laughed.

“That’s Jim,” he said excitedly. “You’ve got to interview Jim. Ask him if he’s voting for Hillary. Just ask him.”

Jim peered down at me from the high cab. He was a big, older guy in his 70s, bald except for some gray stubble that

spread from his dome down to his face, clad in sweatpants and a sweatshirt. His wife sat in the passenger seat, her reddish hair stiff with hairspray. I did what the mechanic said and asked Jim about Clinton. Jim gave me a look of pure disgust.

“I’d vote for the devil himself before I’d vote for that lying, stealing bitch,” he said.

I looked to Jim’s wife for any reaction to the sexist slur her husband used to refer to the first female major party presidential candidate, but she stared straight ahead. I’m guessing she’d heard her husband use that word about Clinton a thousand times while living out their days in some cozy ranch on a couple wooded acres up there in the hinterlands of Northern Michigan. There are thousands of couples like that in the state. You see them eating gravy-covered meals at small town diners wearing boots and insulated flannels. They are retired from well-paying auto jobs and have either moved north to vacationland or are sticking it out in the blue-collar suburbs of Detroit. They play bingo and fish for walleye. They are the “regular Americans” the network media only pays attention to come election time, when television cameras whisk from the coasts into middle America, when those of us in Michigan and the rest of the nation’s interior become “folksy” instead of “flyovers.”

“Did you vote Trump in the primary?” I asked Jim.

“Hell no. I voted Bernie. But I’m voting Trump now.”

I should have known then, in July 2016, that some metamorphosis was taking place. That a toxic anger was fermenting in white guys like Jim and their silent, forward-staring wives.

But I didn’t have any idea it would lead to a Trump victory. Like the rest of the media, I assumed Clinton would clean up on Election Day, but not just because of the disastrously wrong polls. This was Donald Trump we were talking about, whose expressions of incredulous, indecorous incivility could seemingly fill as many pages as Infinite Jest. I had faith not just as a reporter but as a human being and an American that my fellow Michiganders ultimately knew better. That they would see through the charade. That the white, working class families in my beloved home state—who have long been put on a pedestal for their sense of community, humility, and decency—would surely be able to see through a man so narcissistic, prideful, and indecent.

I was wrong.

I failed to see that the election wasn’t just about Trump. It was about anger and hopelessness. It was about Jim and other white voters who felt forgotten, alienated, and ultimately pushed off that pedestal of respect.

In 2016, Jim’s rage trumped everything in Michigan.

I’ve known guys like Jim my whole life.

I was born in Bay City, Michigan in 1977, the year after our state’s previous red dip. In the 1976 presidential election, homeboy Republican hero Gerald Ford cleaned up with 52 percent of the vote while losing to Democrat Jimmy Carter.

It was an era of transformation in Michigan. When I was a kid in the 1980s, an 18-year-old with a high school diploma could still expect to walk into any auto factory and get a job on the spot that would guarantee financial safety for life—a satisfying payoff for the monotony of the work and years of sometimes violent labor struggles.

There was no need to study hard or go to college.

“I’ll just go to the Chevy,” said the older kids who skipped school to smoke pot.

My house was different. Mom and Dad were both from Detroit. Dad had a college degree and worked as a reporter at The Bay City Times for what was then Booth Newspapers, which owned papers in several mid-sized cities across the state, including Grand Rapids and Ann Arbor. It was expected that my brother and I would do more than just graduate high school and get a job at the Chevy. In fact, it was journalism that brought me to Jim’s pickup truck to ask him about his political views this past summer. I now work for the same newspaper chain that once employed my old man.

For most of the year, I’d been hacking away with other reporters at a large investigative project on the Flint water crisis—probably the most chilling story of government failure in our lifetime. We were still working on it during the presidential primaries.

But there was no way Michigan could go for Trump. Not in a million years.

Trump had been around most of my life, of course, flashing his self-satisfied grin in pictures and onscreen, another tanned face in the trash heap of late twentieth-century television culture. I never thought much of him. I never watched his reality show. I never read his books. He was just that rich guy with the atrocious combover who talked a lot. Like much of the world, I was shocked at his rise to power.

Once we wrapped up the Flint project, I thought I’d look into which Michigan county had the highest percentage of Trump voters during the primaries. I crunched the results versus county populations and determined that rural Atlanta, Michigan—an unincorporated county seat located in Briley Township—was our state’s Trump Town. I wanted to touch base with someone up there so, from my home near Ann Arbor—a few hundred miles away—I emailed the township supervisor and the county sheriff. I’m still waiting for the sheriff’s response. The township supervisor, however, emailed me back that same night.

“Yes, I can meet with you,” he said. “Just let me know a time. Don’t bother with a motel. You can just stay the night.”

Michigan has its share of business class Republicans—auto executives, engineers, pizza magnates—who live in the tony Detroit suburbs of West Bloomfield, Birmingham, and the Grosse Pointes. But for the most part, Detroit suburbs aren’t the suburbs of, say, John Cheever. There aren’t many swimming pools. Mom and Dad probably don’t have a college degree. They drink Bud Lite tallboys, not gin and tonics. They live in brick ranch houses where you can vacuum the entire downstairs without changing electrical outlets, not stately colonials. There’s probably a muscle car out in the garage being restored. There’s probably more television sets inside than books.

The last time Michigan turned red—1988 for George H. W. Bush—my family had just moved from Bay City to the Detroit area between the same east-west cross streets of Plymouth and Joy where they’d grown up in the city a few miles to the east. They grew up in the 1950s and 1960s, in the illusory America Trump promises to bring back—a time of strong manufacturing jobs that supported a household with Dad’s one income, clean city streets, and the tacit but unspoken preference of white lives over brown lives in our society.

I joined the renegade crowd growing up. The skaters. The dopers. The punks. The burnouts. We liked drugs, art, and rock and roll. We worked menial service jobs at pizza joints and donut shops—the only kind of jobs around in the 1990s—to support our passions. We snottily stereotyped the working class “Michigan guy.” He worked a trade job—the assembly line, construction, a factory. He played football in high school. He was too macho. He didn’t dance. He drove a pickup truck. He had a fishing boat. He religiously went deer hunting. He listened to country music. Most of all, he had a moustache.

There’s a Nirvana song called “Mr. Moustache.” This is what we called that stereotypical Michigan guy. Mr. Moustache.

I brought along a tent to Trump Country, just in case I ended up camping, a determination I’d make when I saw what kind of hospitality Atlanta, Michigan had to offer. A night on the ground in a state campsite is sometimes better than a cockroach motel. The township supervisor—the de facto mayor—had offered an extra bedroom, but I wasn’t banking on that, either, though I did hope to catch up with him that night because I wasn’t sure if he would evaporate in the morning. Plus, I don’t generally agree to sleepovers until I’ve met someone in person.

I hit the road, I-75 north through Flint, Saginaw, Bay City—towns that peaked twice: first in the lumber era, then the manufacturing era. They aren’t bound to peak again in the near future, though the Mr. Moustaches of the world would like to believe otherwise.

North of Bay City, the terrain changes, as do the attitudes of the locals. This is the area known as Northern Michigan (not to be confused with the Upper Peninsula, which has a different, though related,

cultural identity). People who live in Northern Michigan refer to the urbanized south where I live as “downstate.”

The urban working class isn’t the same as the rural working class, though Trump got both votes. While the Detroit area suffers from stark segregation, the urban working class is made up of many different races and ethnicities. The pay is good thanks to decades of collective bargaining.

The rural working class of Northern Michigan, on the other hand, is almost uniformly white, and lucky to even have a job. Vast stands of white pine used to cover the tip of the mitten until they were clear-cut by the lumber barons of the nineteenth century. It was never very good soil for farming, though hearty folks tried. Now, “Up North” is mostly a tourism economy. The old lumber towns host fishermen, hunters, hikers, bicyclists, bikers, ATVers, campers, off-roaders, boaters, and cottage owners. Many downstaters own a family cottage somewhere “Up North.” The townies work in the hotels, motels, restaurants, bars, gas stations, and golf courses, serving the more well-heeled Michiganders.

Red State Blues

Red State Blues