- Home

- Martha Bayne

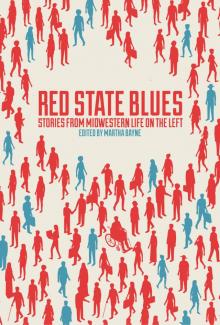

Red State Blues Page 7

Red State Blues Read online

Page 7

“Illinois needs an electoral college,” a Republican friend from Decatur groused after that election.

On a statewide level, that would violate the constitutional principle of “one person, one vote.” So the next year, state rep Bill Mitchell, a Republican from the Decatur area, came up with another solution for ending Chicago’s political dominance over Illinois. He introduced a bill to divide Illinois into two states: one comprising Cook County, the other the remaining 101 counties.

“It’s very simple folks: we just do this and we’ll resemble Indiana more than the present, debt-ridden state of Illinois,” Mitchell said at a press conference to promote his bill. “We can resemble Indiana, which has a lower debt, a lower unemployment rate, and a lower deficit.”

The split between Cook County and the rest of Illinois would be “just like a divorce; there’s irreconcilable differences between the state of Illinois and Cook County,” he said. “Cook County, you go your way. Let the state of Illinois go its way and try to live like a family lives on their own budget. I think it might be in the best interest of both parties to go their own way.”

This was far from the first Illinois secession proposal. In 1925, the Chicago City Council passed a resolution in favor of forming the state of Chicago because rural legislators were refusing to reapportion the General Assembly to reflect the city’s growing population. In the 1970s, western Illinoisans upset over a lack of transportation funding declared their corner of the state “the Republic of Forgottonia.” In 1981, state senator Howard Carroll of Chicago actually passed a Cook County secession bill through both houses of the General Assembly, just to scold downstaters who were complaining about funding Chicago’s mass transit. (It was pulled back by then house speaker George Ryan.) Even if a bill were to pass, dividing Illinois would require the consent of Congress. (In our internet era, this view is represented by the Southern Illinois Secession Movement, whose Facebook page has 106 followers.)

Since downstaters complain so often about sharing a state with Chicago, it’s important to remember that they wanted it this way. Nathaniel Pope of Springfield was the territorial delegate to Congress in 1817, as Illinois was preparing to enter the union. Pope wanted Chicago for the very same reason Mitchell wanted to get rid of it: because it adds a metropolitan, northern character to Illinois.

Originally, the Northwest Ordinance, passed by the Second Continental Conference in 1787, declared that Illinois’s northern border would run along a line defined by the southern tip of Lake Michigan. Had that plan been followed, it would’ve stretched from Calumet City to Moline. What we now know as Chicago would’ve been part of Wisconsin.

Pope proposed pushing the boundary line north. There were both commercial and political advantages to possessing a Lake Michigan port. The new state could build a canal connecting the Mississippi Valley to the Great Lakes. Most of the Illinois Territory’s early settlers were southerners. Pro-slavery sentiment was strong. But since Mississippi had just been admitted to the union, and would soon be followed by Alabama and Missouri, it was essential that Illinois be a free state to preserve the balance in the Senate. Pope wanted to attract Yankees migrating westward across the Great Lakes.

At the time, of course, no one knew that the trading post at the mouth of the Chicago River would burgeon into one of the world’s great cities. But Pope realized it would be essential to shaping the state’s character.

Even so, throughout the 20th century, Illinois political power was closely balanced between upstate and downstate. The Republican Party dominated the Chicago suburbs and the farm counties, while the Democratic Party held sway in Chicago and Little Egypt (as southern Illinois is nicknamed, possibly because the meeting of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers is said to resemble the Nile Delta). As a result, “downstate was the swing area,” says Kent Redfield, a former legislative staffer and professor of political science at the University of Illinois at Springfield. “Having downstate candidates was important for balancing the ticket.”

That need for geographic diversity helped build the political careers of such influential downstaters as Democratic senators Alan Dixon and Paul Simon and Republican governors Jim Edgar and George Ryan. But at the beginning of this century, as the rest of the nation divided itself into urban blue and rural red political enclaves, Illinois did the same. The Chicago suburbs became more ethnically diverse, and college-educated professionals repelled by the Republican Party’s virulent Bible Belt conservatism began voting Democratic. Meanwhile, downstate became more Republican, as college graduates left the region and the loss of coal and factory jobs decimated labor unions that had formed the bulwark of the Democratic Party. When Bill Clinton won Illinois in 1992, he carried Chicago and downstate Illinois while losing most of Chicago’s collar counties. In 2016, Hillary Clinton carried all of northeastern Illinois but won only a handful of downstate counties—those containing cities and/or college campuses. (Clinton began her political career in 1964 as a “Goldwater Girl” from once staunchly Republican Maine Township—which voted for her by 20 points.)

“Downstate is solidly Republican, but it’s much less important,” Redfield says. “Look at the legislative leaders.” House speaker Michael Madigan and senate president John Cullerton hail from Cook County. So do the last three governors: Rod Blagojevich, Pat Quinn, and Bruce Rauner. The only downstaters currently holding statewide office are state treasurer Michael Freirichs of Champaign and Senator Dick Durbin of Springfield.

No place exemplifies downstate’s changing political and economic fortunes better than Decatur, the hometown of secessionist Bill Mitchell. I lived in Decatur in the mid-1990s when I was a reporter for the local newspaper, the Herald & Review. At the time, it was a heavily unionized town loyal to the Democratic Party. But it was undergoing a series of labor disputes that made it a “flash point of globalization,” according to its then congressman, Glenn Poshard. Tate & Lyle, a British company that had bought Staley, provoked a strike that lasted two and a half years—one of three labor disputes that resulted in a drastic reduction of union jobs in Decatur. Workers at Decatur’s Caterpillar plant went on strike. So did workers at the city’s Firestone plant, which eventually shut down after a scandal over faulty tires. Decatur is now Illinois’s fastest-shrinking city. Macon County delivered majorities for Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, but it voted 55 percent to 38 percent for Donald Trump, who promised to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement and other Clinton-era trade deals that he claims have hollowed out midwestern factory towns. (NAFTA, which was unpopular with unions from the start, has been blamed for allowing Maytag to move refrigerator production from Galesburg to Mexico, and for Roadmaster moving bicycle production from Olney to Mexico.)

“I backed Bernie Sanders,” says Jay Dunn, the Democratic chairman of the Macon County Board. “I had to hold my nose to vote for Hillary; a lot of people didn’t hold their nose and voted for Trump.”

Beyond its loss of blue-collar union jobs, Decatur also lost a significant element of its professional class when its most important food-processing companies, Tate & Lyle and Archer Daniels Midland, moved their headquarters to Cook County, which is more appealing to the executives it wants to attract. (Caterpillar recently moved its headquarters from Peoria to Deerfield.)

“That didn’t help the feelings of the Decatur people, losing the status of that,” Dunn says. “The economic part of it is we’ve lost a lot of air traffic, people flying in to visit the president and the higher executives. Our airport’s kind of struggling. Houses are sitting empty, because most of the executives lived in expensive houses. It’s stupid to blame Chicago, though. The company’s just making business decisions. ADM and Tate & Lyle are international businesses. People flying in, there’s not a lot to do in Decatur, Illinois, compared to Chicago.”

Dunn also disagrees with downstaters who think they’d be better off if they didn’t have to share a state with Chicago.

“We got some people who just hate Chicago, ignorant o

f the fact that without Chicago, we’d all be broke,” he says.

In 2016, Governor Rauner tried to inflame the Chicago-downstate divide. Speaking at a prison in Vienna, he attacked a $900 school bailout plan that would have devoted more than half its funds to the Chicago Public Schools. “The Senate and House are competing with each other [to see] who could spend more to bail out Chicago with your tax dollars from southern Illinois and central Illinois and Moline and Rockford and Danville—the communities of this state who are hard-working families who pay their taxes,” Rauner said.

“Rauner’s rabble-rousing against Madigan and the mythical Chicago machine, which is informed by polling and focus group data that I don’t have, suggests that the ill-feeling remains general enough to be exploitable,” James Krohe Jr., author of Corn Kings and One-Horse Thieves: A Plain-Spoken History of Mid-Illinois, published by Southern Illinois University Press. “Chicago and downstate are like conjoined twins, one of whom has a weak heart and is being kept alive at the expense of his stronger sibling. Great swaths of downstate are dying, demographically and economically; parts of the region remain viable only because assorted transfers of wealth from greater Chicago and Washington sustain it in the form of social security and disability checks, crop supports, and university and prison funding. (Deep southern Illinois, for example, has only two industries worthy of the name: SIU and road building.)”

If legislators actually did divide Illinois into two states, one comprising the six counties of the Chicago area, the other comprising the rest of the state, here’s what each would contain, and contribute. Downstate can keep the name, since the Illinois (aka Illiniwek) Indians didn’t live up here. Chicagoland would call the new state Potawatomi.

Population

Potawatomi: 8.3 million

Illinois: 4.5 million

Fortune 500 companies

Potawatomi: 30

Illinois: 2 (State Farm, John Deere)

State universities

Potawatomi: 4

Illinois: 8

Prisons

Potawatomi: 1

Illinois: 40

State parks

Potawatomi: 6

Illinois: 35

Per capita income

Potawatomi: ranges from $23,227 in Cook County to $35,546 in DuPage County

Illinois: ranges from $13,325 in Pulaski County to $23,173 in Sangamon County

Tax revenue

Potawatomi: $10,207,787,779

Illinois: $4,485,087,020

Gross state product

Potawatomi: $532 billion

Illinois: $120 billion

“Once upon a time, Chicago and downstate belonged to the same economy,” says Richard C. Longworth, author of Caught in the Middle: America’s Heartland in the Age of Globalism and a fellow at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. “Factories downstate made things Chicago needed. That’s gone away. What’s replaced it in Chicago is the global economy. What economic vitality there is in Illinois is in Chicago. The economic fortunes of Chicago and downstate are diverging.”

Obviously, a lot of downstaters are mad as hell about losing political and economic influence to Chicago. But do Chicagoans even notice? And if they notice, do they even care? No, and probably not. Culturally, Chicagoans don’t identify with—or even think much about—the state they inhabit. As a friend puts it, “I’m not an Illinoisan. I’m a Chicagoan.” I once mentioned to another Chicago friend that I’d just visited a small town in southern Illinois, “down by the border with Kentucky.” She looked at me quizzically. “Illinois doesn’t have a border with Kentucky,” she said. (This is someone with a master’s degree—but not in geography.)

If someone tells you, “I’m from Illinois,” it means that (a) he’s not from Chicago, and (b) he’ll be annoyed if you ask. (Matt Weidman is from Berwick. As he puts it in the bio of his Twitter feed, @forgottonia, “Is that near Chicago? NO, it is not.”) Kevin Cronin, the lead singer of Champaign’s REO Speedwagon, once introduced “Ridin’ the Storm Out” in concert with a story about how it was inspired by a Rocky Mountain thunderstorm, an astonishing sight for “an Illinois band.” (Another musician who tried to promote pan-Illinoisism: Musician Sufjan Stevens (who was born in Detroit) offers a pan-Illinoisan view in his album Illinois, which includes songs about Decatur, the Rock River Valley, and Metropolis as well as Chicago.) But Chicago’s lack of identification with the rest of the state has prevented Illinois from developing a distinct identity like that possessed by so many of its neighbors. Wisconsinites drink beer, fish for muskie, and drive snowmobiles across frozen lakes. Minnesotans are passive-aggressive, play hockey, and eat hotdish. Iowans grown corn and sculpt butter cows. What does it mean to be an Illinoisan?

“When I’m in other states, and I say I’m from Illinois, the first question I get is ‘How far is that from Chicago?’” says East Saint Louis native Ray Coleman, who helped sell Barack Obama’s 2004 Senate candidacy to downstate voters. “Chicago always comes up in the conversation. In Metro East”—the trans-Mississippi suburbs of Saint Louis—“everybody feels forgotten. It’s Chicago, the collar counties, and that’s all that matters.”

This ignorance is partly a result of the fact that Chicagoans don’t consider the downstate Illinois a vacation spot—it’s flat, it’s hot, it doesn’t have any big lakes. Chicago is a Great Lakes city, so it’s more convenient, and more congenial, to spend a weekend on the water in New Buffalo, Michigan, or Door County, Wisconsin, than on the Mississippi River—even though Illinois has more miles of Mississippi riverbank than any state. Dan Krankeola, president and CEO of Illinois South Tourism, which serves 22 counties south of Interstate 70, says he barely bothers marketing to Chicago.

“We find the majority of our tourists are coming from Saint Louis, Indianapolis, and farther south of us,” Krankeola says. “If you live in a big city, you love that environment. Our character is very different from Chicago.” (If you’re thinking of heading downstate, Krankeola says, “We’ve got a World Heritage center at Cahokia Mounds; we’ve got Gateway Motor Sports Park, Shawnee Hills Wine Trail, Carlyle Lake Wine Trail. A lot of opportunities for a staycation.”)

It literally took an act of God to lure Chicagoans to downstate Illinois. That act was this year’s so-called Great American Eclipse, whose path crossed far southern Illinois on August 21. Chicagoan Eric Bremer and his wife, Helen, went to see the rare spectacle. A Decatur native whose grandparents lived in Metropolis, Bremer was familiar with Little Egypt, which lies in the northern salient of the Ozark Mountains, but it was a revelation to Helen.

“I think it was one of Helen’s first trips,” Bremer says. “We went down, and I sort of forgot—you get down into the Shawnee, and it’s very different, and it’s not the Illinois that you think about. We went to Bald Knob Cross, which was fantastic for eclipse watching. It’s beautiful, looking around there and seeing the valleys. It’s a different world, even culturally, because it’s entwined with the Ohio River and the Mississippi Valley. She had no idea that sort of place existed in Illinois.”

Bremer is already planning a return trip, to the New Columbia Bluffs, in Massac County, which mark the northernmost range of southern flora and fauna, such as bald cypress, magnolia—and poisonous snakes. (One of the last remaining tourist attractions in Cairo is Magnolia Manor, a 19th-century mansion with the namesake tree growing in the front yard.)

When Chicago alderman Ameya Pawar was growing up in the north suburbs, his family vacationed on Michigan’s Mackinac Island and at Niagara Falls, but rarely ventured downstate. So when he launched his shortlived 2017 campaign for governor, Pawar made it a point to venture into “Forgottonia.” He even chose as his running mate the mayor of Cairo, a town as close to Jackson, Mississippi, as it is to Chicago. They bused Cairo public housing residents to the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s office in Chicago to protest plans to close down their buildings and scatter the residents. Many were making their first trip to Chicago. On his downstate c

ampaign stops, Pawar inevitably had to overcome local suspicions of the “corrupt Chicago politician,” but once he did, he found commonalities between the two spheres of Illinois. Galesburg, which lost its Maytag factory, and Newton, which lost a Roadmaster plant, are undergoing the same economic dislocation as the south side of Chicago when the steel mills shut down in the 1980s.

“Cairo, East Saint Louis, the south and west sides of Chicago, Freeport, Galesburg—they’re all dealing with the same problems of disinvestment,” Pawar says. “The assumption is that people there are weak. But these communities often have the most resilient people, because they have to stitch things together after government has left them behind. What happened 40 years ago in black and brown communities is happening now in small towns, with the opiate crisis. Now it’s considered a public health problem.”

One of Pawar’s campaign themes was “One Illinois.” After ending his campaign, he announced the formation of a political action committee with that name. And in February 2018 he announced the launch of a media platform as well.

“I want to bring people together from small towns and big cities to tell stories about what it means to be an Illinoisan,” Pawar says. “Bring people together, and you can say, ‘Look, let’s see the commonality. The economy changed. Why are we fighting each other? Why are we allowing our leaders to tell poor whites that black and brown people are a threat to them? We end up fighting around race, class, and geography when really it’s the system that’s the problem.”

In 2012, Pawar was part of the inaugural class in the Edgar Fellows Program, which brings young leaders from around the state to the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign for a series of seminars hosted by former governor Jim Edgar.

“On our second day of the fellowship, Governor Edgar put all of us on a bus and he’s like, ‘Look, I want to take all of you to a working farm,’” Pawar says. “So he goes to a farm outside Champaign. He looks at the Chicagoans and said, ‘I’m glad you got to see a working farm. What’s grown on this farm gets traded on LaSalle Street.’ Then he turns to the rest of the fellows. ‘You’ve got to stop complaining about the CTA getting funding. The structure that supports LaSalle Street doesn’t exist without the CTA. If there’s no LaSalle Street, you have no place to trade your grain.’”

Red State Blues

Red State Blues