- Home

- Martha Bayne

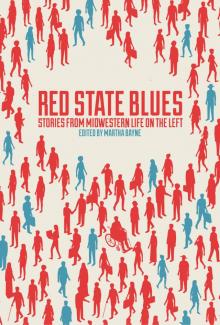

Red State Blues Page 6

Red State Blues Read online

Page 6

“Oh, no! That’s not true. They just get tricked into thinking it’s their choice,” Connie said with the same gentle yet self-assured firmness one uses to explain “stranger danger” to a child. I can still see Sarah, our tattooed teen girl coworker nodding in solemn agreement. What struck me most in that situation was how these two women who usually hated each other’s guts were suddenly united in their shared assumption that all Muslim girls are victims. That’s what I think of whenever I hear the term “white feminism.”

That job was my first lesson in the way white outsiders perceived the post-white neighborhood where I was raised. And more often than not, the outsider perspective was (and still is) quite racist. But dealing with those awful white librarians had to be way worse for Sam, who worked there at the same time I did. He and I remain good friends today and I chuckle remembering one of his observations about the 2016 presidential primary election. He compared every Republican candidate to the worst faculty members at our high school. Jeb was the bumbling guidance counselor, Rubio was the slick young science teacher, Trump was the sleazy, out-of-shape gym teacher.

“And Hillary,” he said, “is every awful white woman who worked at the library.”

Just days after he said that, I saw footage of Clinton in a coffee shop, sneering at a Somali-American woman who questioned her support of black communities. “Why don’t you go run for something then?” she responded to the young lady with a dismissive chuckle. The expression on her face immediately reminded me of the way some librarians would talk down to Sam. And it also reminded me of Connie and Sarah lamenting the poor, misguided hijabis. One of the perks of white feminism is that when women of color disagree with your actions or your worldview, you think you can treat them like idiot children.

A week after that Hillary video went viral, Dearborn’s Arab-Americans and Muslims voted overwhelmingly for Bernie Sanders, helping him achieve his unexpected win in Michigan’s primary election. Many pundits were stunned to see this community throw their support behind a Jewish candidate, but assuming the opposite result only makes sense if you also assume this community is necessarily anti-Semitic. Hillary Clinton’s primary loss in Dearborn makes more sense if you consider her history of policy affecting the Middle East—from voting for war in Iraq to embracing the use of drone warfare during her tenure as secretary of state.

I’ve been living in the South for the past seven years, and anyone down here who’s heard of Dearborn knows it mainly as a Muslim enclave. A few years ago I met a Michigan guy at a bar in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and when I told him I was from Dearborn, I swear his immediate response was, “Dearborn’s changed, huh?” Groan. I’m always quick to explain, perhaps a bit defensively, that growing up there and attending diverse schools was good for me.

But the simple fact is that I love my hometown because it’s where I’m from. I spend a lot of time in Dearborn whenever I go back to visit family and friends. The familiarity of it comforts me, even the gridlike streets and cookie-cutter tract housing that I found so dull and stifling when I was young. But mostly I enjoy the people, the blunt and funny yet easygoing manners that remind me of the best parts of high school. Southeastern Michigan will always feel like home to me. Even from hundreds of miles away, I still care what happens to metro Detroit as it reimagines itself in this post-industrial economy.

So I follow news from that region, which is how I happened to notice a Twitter post from a Detroit Free Press journalist just days before the 2016 presidential election. “Hillary Clinton came to Dearborn today, but like her husband in March, goes to west side place, avoids mosques, Arab centers, Muslim clergy.” And in the tweet quoted beneath his post were the words, “Clinton swung by Miller’s bar in Dearborn, Michigan this evening.”

I literally screamed. It was too perfect. I messaged Sam with a screen cap of the tweets and the words, “FUCKING MILLER’S” He replied with an “LOL.” We traded jokes about the stupid, infamous burgers and the librarians who loved them. We prayed that Hillary would beat Trump anyway, but I remained bitter.

“I swear it’s a dog whistle,” I told my husband. And instinctively, I still believe that. Clinton took the Arab and Muslim votes for granted. She laid all her money on those white swing voters and she met them at a place that remains, to this day, a landmark for west Dearborn’s shrinking white population.

I’ll fully admit that I’ve never been to Miller’s, but as far as my subconscious mind is concerned, it’s a “safe space” for every white person who’s ever sighed and uttered the words, “Dearborn’s changed.”

SEVEN YEARS IN INDIANAPOLIS

ALLISON LYNN

When I moved to Indianapolis in 2010, I imagined myself as an anthropologist—which, in retrospect, is a pretty rude way to move anywhere. But I was a native Northeasterner: I spent my childhood in Massachusetts, went to college in New Hampshire, and then lived for nearly two decades in New York City before my husband and I relocated to Indianapolis for university teaching jobs. With those jobs came the promise of no longer having to panic every time the rent was due, but at the cost of leaving my liberal bubble.

Sure, there had been Republicans in my circle in New York, but even at the time I understood that they were fake Republicans: socially liberal or financially greedy voters looking out for their own interests. One hedge funder I knew openly talked about how he intended to switch his party registration from Republican to Democrat as soon as he’d socked away his millions. He wasn’t a real Republican, just an idiot.

Another woman-in-media friend attempted to vote in the Republican primary, only to find that her Greenwich Village polling place had no machines set up for GOP voters. “We didn’t expect any,” the poll workers apologized, giggling amongst themselves. On her walk home that day, my friend asked herself why, in fact, she was still registered Republican if she was pro-choice, pro-woman, and pro- so many other equal opportunities. She switched parties before the next election. She wasn’t a real Republican, just lazy.

But now, four decades into my life, I’d be moving to a place with actual Republicans as my neighbors. I steeled myself for debate and argument and a reckoning with why, exactly, so much of the country voted in ways that seemed a mystery to me.

Bring it on, I thought as I packed the car and headed west.

In his 2006 profile of Axl Rose in GQ magazine, John Jeremiah Sullivan writes: “Given the relevant maps and a pointer, I think I could convince even the most exacting minds that when the vast and blood-soaked jigsaw puzzle that is this country’s regional scheme coalesced into more or less its present configuration after the Civil War, somebody dropped a piece, which left a void, and they called the void Central Indiana. I’m not trying to say there’s no there there. I’m trying to say there’s no there.”

My first year in Indianapolis, I thought I understood what Sullivan was talking about. I had come to Indianapolis with my liberal talking points in hand, ready to argue and yell and maybe, after a few of the excellent Indiana microbrews I’d been reading about, to even listen to a different point of view. Quickly, though, I discovered that there were no raging arguments or debates at my local pub, and my new neighbors, if they were the ultra-conservative radicals I had expected, weren’t talking about it. Instead, the populace was quiet.

And frankly, so was the downtown scene. In fact, there was no sense of an active downtown at all. The city as a whole felt numb. When I asked where to eat, more than one local told me to head three hours up to Chicago for good food. As for shopping, a West Coast transplant explained to me that “Indianapolis is a good place to live, value-wise, but we do our consumption elsewhere, when we’re in California or New York.”

By my second year, though, Indianapolis began to undergo a dramatic cultural change, so much so that central Indiana was no longer a place you’d feel entirely comfortable describing as a void. Things peaked when chef Jonathan Brooks opened the restaurant Milktooth—serving modbar espressos and bruléed grapefruit and miso soup with pickled k

ombu—and landed on Bon Appetit’s list of “10 Best New Restaurants in America.” Down the street from me, Benjamin and Janneane Blevins opened a bookstore called Printtext in a whitewashed single-room storefront whose tables were piled with stacked issues of Dissent and n+1 and Cherry Bombe and vintage literary magazines and journals where the essays appeared in both Lithuanian and English.

The there that began to fill in around me resembled more and more the there familiar to those of us from elsewhere. The city suddenly seemed full of hipster Latin-fusion restaurants and artisanal donut shops and experimental food trucks and legitimate tacos. As I type this, a restaurant serving $85 omakase meals is getting set to open.

My fourth year in the city, I was invited to an Easter egg hunt (chocolate eggs and coolers of microbrew) in my neighborhood, where the other guests were longtime Hoosiers, all of whom vote blue. This blew apart my theory that the blue streak running through Indy was entirely powered by transplants (the same transplants who were eating the legit tacos and Latin-fusion but couldn’t quite keep all of the artisanal donut shops in business). And it reminded me of all the judgmental shit I’d cast on Indianapolis before I arrived. So maybe it’s not that Indianapolis was undergoing so much change, at its core. Maybe it’s that I’d finally lived long enough in the place to begin to understand it—a process that doesn’t take months, or years, but years-and-years-and-years. Especially in a city where so much of what’s going on is under the surface.

I’ve been assured by people who’ve been here for decades that the food scene really is getting better. The food scene as a culinary development, they mean, not as an indicator of some sort of swing toward blue politically. The microbrew-swigging egg hunters assure me that city’s blue streak has a long history. Because while the city voted red in nearly every presidential election prior to 2004 (and has voted blue since), the democratic slice of those pre-2004 elections consistently hovered at around forty percent—sometimes nearing fifty. That’s not nothing. Especially in a state known as a conservative stronghold.

What is new, I’d argue, is the volume of that blue-streak’s voice. Thanks to Mike Pence’s attempts as Governor to wrest the state even further to the right, the political numb silence that greeted me in 2010 was replaced by serious Midwestern can-do in 2013. My neighbors rallied and wrote letters in support of same-sex marriage. Lawns on my block sprouted signs that read “Pence Must Go” and “Fire Pence: Your Rights Could Be Next.” My son, age 6, begged for an “Expel Pence” sign for his birthday. Everyone else already has one, Mom!

I started to understand that if Indianapolis is a blue bullseye in the middle of this doggedly red state, the bullseye grows bluer and bluer as you move toward its center, until you come to its very, very middle: the streets where my house sits. When I first moved in, a new friend described a woman on my street as “a good Democrat”—her way of explaining that the woman was someone I’d be glad to know.

It’s easy, as I write this from that street, to think the new blue voice has grown deafening. It’s only when I venture into the outer rings of the bullseye and beyond, that I’m reminded how truly atypical my neighborhood is. This grand change, this opening up, this loud blueness, this application of Midwestern can-do to defeating the far right—it isn’t happening all over. Drive an hour west of Indianapolis and, in reaction to the South Carolina statehouse debate, you’ll see trucks flying Confederate flags. In Greencastle, students of color tell me they’ve been pelted with sodas thrown from the windows of those same pickup The Indiana I’ve experienced these last seven years is not the same that others know.

I was out of the country during Trump’s election. I had been in Paris for the year, where my husband and I were working on books. In the months after the vote, I commiserated with French friends, who themselves were nervous about Brexit and the specter of Le Pen. I traded worst-case-scenarios with the expats I knew—mostly other parents of kids at my son’s French (with a bilingual-English bent) school. We protest-marched together and followed Twitter and talked theories about the election during school potlucks. At one afternoon pickup in December, I was cornered by two dads, both American.

“You must know lots of people who voted for Trump,” they said, “in Indiana, and all.”

But here’s the thing: I couldn’t think of a single one. I explained this to them using the bullseye metaphor, a metaphor that quickly expanded into some sort of theory about the widening divisions in our country as a whole.

When I moved back to Indianapolis in the summer of 2017, I still couldn’t think of a single person I knew who would have voted for Trump. With this in mind, I attended a fundraiser for Rep. Andre Carson, the Democrat who represents the streets just south and west of mine—though my house falls one block into the district of Republican Susan Brooks. I arrived to the fundraiser feeling good. Our city’s got a Democrat in the House, and all of us who were gathered want to prop him up. There are a lot of us on the left, my friends and I told ourselves. We just need to ensure we’re heard. But then a young campaign donor asked Carson how he should talk to his own family members in the south of Indiana. He said that outside of Indianapolis, everywhere he goes all he meets are Trump voters who, nearly a year into this disastrous presidency, still see Trump as some sort of hero. “What should I say to them?” the young Democrat asked Carson.

Carson didn’t have an answer.

How do we talk to them? is really what the guy wanted to know.

It seems increasingly the answer is that we don’t.

In Indianapolis—in all of the Indianapolises in America’s Midwest—we’re getting better food and leftist bookstores and expanding contemporary art scenes and choosing, so often, to read this as a new political reality. But these bookstores and art scenes and pour-over coffee bars aren’t replacing what was here before. They’re co-existing just out of eyesight. We’re two sides at a standoff with a wall between us—to use the right’s terminology—preventing us from even seeing each other.

What it boils down to, it seems, is that there are two Indianas just as there are two Americas. And there are two Indianapolises, as well. The city is home to Democrats who are museum fundraisers and poets and sound artists and fiction writers and lawyers and bankers and CFOs. We are transplants and natives and teenagers and retirees. And we are surrounded by churches full of Republicans, by art classes packed with GOP-leaning novice painters, by right-wing financial managers, college students, and orthodontists. Conservative marketing professionals drive past my house to go to work downtown every day. Even if our voice as Democrats is amplified in this city, it remains barely a whisper in the greater fact of our state.

So if I’m still pretending to be an anthropologist, what have I found? Seven years in Indianapolis, and what I’ve come up with aren’t answers, but questions: What happens when one Indianapolis stops talking to the other? What happens when there are evangelicals next door but you no longer hear them? When you no longer even see each other? Where does this leave us? Where does it lead?

DOWNSTATE HATE

EDWARD McCLELLAND

PREVIOUSLY PUBLISHED IN THE CHICAGO READER, NOV. 15, 2017

On an Amtrak platform in Springfield, I met that rarest of an Illinoisans: a woman who divides her time and her loyalties between downstate and Chicago. Pat Staab lives in the state capital most of the time, but she was on her way to Chicago, where she keeps a condo in River North.

“I’m from New York,” she told me. “I need a big city.”

As a result of her peregrinations between upstate and down-, Staab is well versed in how the state’s rival regions view each other. Downstaters think Chicago is “crime—you’re gonna get mugged,” she said. Chicagoans think downstate is “rural, all farms. I tell them we’ve got museums here. We’ve got a symphony.”

“There are people from Springfield who’ve never even been to Chicago,” Staab said.

“I’m sure there are people from Chicago who’ve never been to Springfield,” I replied.

“Except maybe on a field trip.”

The animosity between Illinois’s largest city and its smaller towns is almost as old as the state itself. I say “almost,” of course, because Chicago, incorporated in 1837, is 19 years younger than Illinois, which is set to begin a yearlong celebration of its bicentennial on December 3. Downstaters have always thought of Chicago as a black hole of street violence and political corruption, sucking up tax dollars generated by honest, hard-working farmers. Chicagoans have always thought of downstate—when they’ve thought of it at all—as an irrelevant agricultural appendage full of Baptists and gun owners who’d just love to turn Illinois into North Kentucky.

For most of Illinois’s history, the two spheres have been evenly matched in influence, with downstate contributing some of Illinois’s most important political figures, from Abraham Lincoln to Adlai Stevenson. Downstate was also the forcing ground of internationally known industries: Moline gave us John Deere, Peoria gave us Caterpillar, and Decatur gave us Staley, which in 1920 hired George Halas to coach a company football team he would move to Chicago the following year and rename the Bears.

More recently, though, the misunderstandings and alienation between Chicago and downstate have been ramped up by two particularly 21st-century phenomena: globalization and political polarization. As the big global city in the northeastern corner of the state sucks jobs and college graduates out of the rest of Illinois, downstate is becoming older, less educated, less prosperous, more reactionary, and more Republican. Politically, downstate is in complete opposition to the Chicago area, especially on such culturally charged matters as gun rights, LGBT rights, and abortion. But it lacks the votes to bend the state to its will on any of those issues. This was never more evident than in 2010, when Governor Pat Quinn defeated state senator Bill Brady, a social conservative from Bloomington, despite carrying only four of the state’s 102 counties—and could’ve won by carrying only Cook County.

Red State Blues

Red State Blues